Bill Paxton at KITP. Photo credit: Matt Perko

Bill Paxton at KITP. Photo credit: Matt Perko

Bill Paxton ingrained himself into astrophysics, and into the astrophysics community, in an indelible manner. His curiosity and passion have left an enduring imprint on the field. Over 520 students have been trained at MESA summer schools, and the MESA instrument papers have accumulated more than 14,000 citations.

“There are things that are impossible to quantify, though,” said Meridith Joyce, an assistant professor at University of Wyoming. Like the professional collaborations he forged and the lasting friendships he fostered.

Friday November 21, 2025 was a day to celebrate Bill, who passed away in July. The afternoon witnessed moments of thunderous laughter and teary emotional breakdowns.

“Long before Bill was a rockstar in the firmament of theoretical physics, he was a pioneer in developing all the things [in computing] that we use and take for granted today,” said his colleague and longtime friend Jim Mitchell. From his involvement in the Mother of All Demos, to the invention of PostScript and the development of the PDF, Bill revolutionized the field of computing.

And yet, after all this, he embarked on an entire second career to no less success. Bill’s was a mind that wouldn’t be left idle. “I just remembered him one time saying, ‘Well you know, I think I’ve decided to learn physics. So, I’m reading a Physics 1 textbook,’” recalled close friend and colleague Ann Robinson.

Well, Bill was never one to dabble, so he soon found himself in class. Tony Piro, at Carnegie Observatories, recalled walking into an upper-division class in the spring of 1999. “Among all the students was a somewhat older man wearing metal-rimmed glasses and a distinguished beard.”

Bill bucked the stereotype of retirees who audit university classes. His long, handwritten problem sets were among the most meticulous of anyone in the class. Tony and Bill continued up the physics course ladder together. And when Tony returned to UCSB to pursue his Ph.D. with Professor Lars Bildsten—a KITP permanent member at the time—“lo and behold, Bill was back for graduate school as well!”

Bill’s “superb retirement project,” as Jim Mitchell described MESA, became the foundation of modern computational stellar astrophysics. And the enterprise has created a community of friends and collaborators around the world.

Many of Bill’s relationships were stories narrated in email, from first introductions years ago to many final farewells during the day’s events. “We started with an email, and over the ensuing decades we exchanged approximately 20,000,” remarked MESA co-developer Frank Timmes (Arizona State University).

On January 8, 2005, Frank received an innocuous message that changed the course of his life:

“Hello, my name is Bill Paxton. May I please use the tools posted on your website?”

Three things immediately stood out to Frank: The message was extraordinarily polite. It also actually asked to use his code. “Nobody asks,” Frank said. “They just take it and go.” And it had a KITP web address. So, he thought, “Okay, Lars has a new grad student.”

“About three emails later…I’m going, ‘This is no grad student, is this,” Frank recalled. Even in 2005, it didn’t take too long to figure out who Bill Paxton was. “I remember thinking to myself, ‘Wow, we got a ringer on the line here.’”

Many who knew Bill would also relate with the introduction provided by co-developer Rich Townsend of University of Wisconsin-Madison: “I’m going to talk about how Bill completely derailed my career.”

Bill enticed people with intriguing questions that then grew to become challenging projects. But by the time you realized what had happened, you were too invested to leave. “When you start working with [him], it’s like you jumped on a rollercoaster,” Rich said. “Wherever you [were] going, you are not going there anymore. You are going somewhere else, and you are going somewhere else fast.”

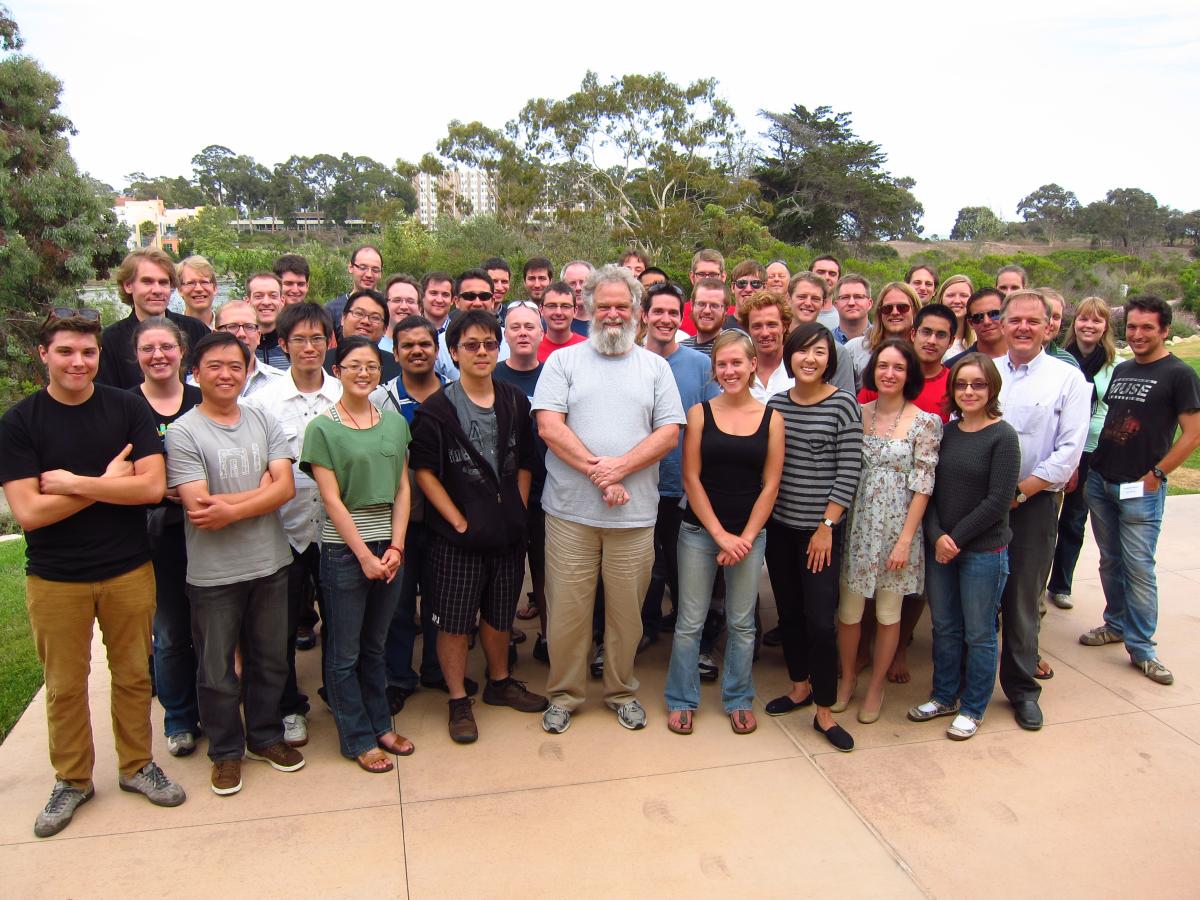

The first MESA Summer School, August 2012. Credit: Frank Timmes

The first MESA Summer School, August 2012. Credit: Frank Timmes

While new riders on the Bill-ercoaster may not have known where they were headed, they certainly weren’t going alone. Bill would see them through the track’s twists and turns—many put there by Bill himself—not so much as a pilot but as a guide.

Bill pushed people to do things they didn’t believe they were capable of; things they may not have had the courage to attempt on their own. “He expected so much more of all of us…than we expected of ourselves,” Rich said. Time and again he demonstrated that a cantankerous streak was no barrier to mentorship and generosity. And that patience and hustle were complements, not opposites.

“Bill didn’t really go easy on people,” said co-developer Jared Goldberg, currently at the Flatiron Institute. But rather than seeking to cut ideas down, his relentless skepticism served to build people up. As Bill once told Jared, “I’m not asking you because I think you’re dumb. I’m asking you because I think you’re smart, and I want you to explain this to me so that I can understand it.”

That said, Bill would absolutely rewrite your code from the ground up rather than try to debug it. Gia DePalma singled out four traits to describe her grandfather: generous, passionate, stubborn, and brilliant. You’d be hard-pressed to find any more fitting.

KITP Director Lars Bildsten tried to encapsulate his long, fruitful collaboration with Bill in a few words he saved for after the event. “I worked closely with Bill for over 20 years. He was the deepest scientific collaborator in my life, and I miss him every day,” Lars said. “Especially on Saturday mornings, when we would typically engage for a few hours of vigorous scientific debate.

“No one else in my scientific world was as deliberate in thought, purity of calculation and language,” Lars continued. “He did not happily tolerate loose language or, worse, loose thinking! This sharpened all of us who had the privilege of working with him.”

Bill’s zeal, coupled with his brilliance, meant that he simply didn’t see the barriers that others tried to point out. It made him an effective mentor, a formidable teammate, and an astounding personality to behold. And it meant that he seemed capable of nearly anything, like a plainclothes wizard. His family, friends, and colleagues likely wouldn’t be surprised if Bill becomes bored of his current occupation and, one day, returns unannounced to continue where he left off, with a smile on his face and a twinkle in his eye.

by Harrison Tasoff

Science Writer, UCSB Public Affairs & Communications