The KITP web site is the opposite of “all-show/no-go.” It may, upon first inspection of the homepage, look like a humdrum vehicle analogous to the base-model Ford pick-up, circa 1997. But under that dated hood, so to speak, lies the visionary apparatus of the virtual KITP — a 10-year archive of scientific talks (now averaging 1,000 a year) ready for access worldwide in a number of formats variously combining audio and visual information for user reenactment.

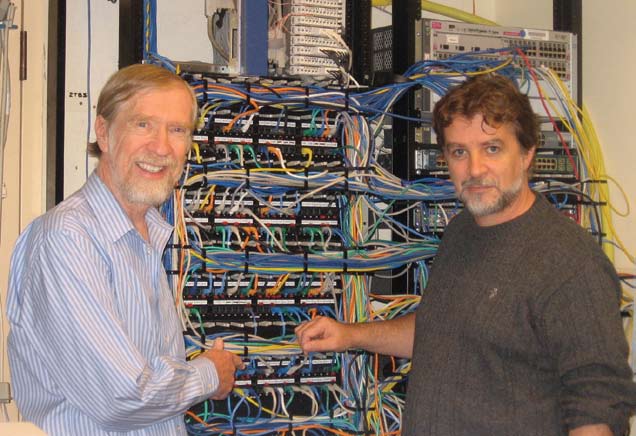

Presiding over the virtual KITP is web wizard and UCSB physics professor Douglas Eardley. It is, literally, his creation as well as his province, though he insists that he couldn’t have done it without the able assistance of the KITP computing staff, especially its leader, Kevin Barron.

According to another visionary on-line archivist and physicist, Paul Ginsparg, “The KITP talk archive is both an extraordinarily useful resource and an extraordinary proof of concept.” Ginsparg developed the “arXiv,” which sounds like and is an “archive” for electronic preprints of scientific papers in physics, mathematics, computer science, and quantitative biology.

Observing that the KITP’s “on-line talks provide a surprisingly effective source of information otherwise unavailable,” Ginsparg noted, “It helps that the KITP seminars are uniformly of the highest quality, given by experts in every field, and the visual and sound quality is also more than adequate.”

Ginsparg, professor of physics and computing and information science at Cornell, pointed out, “Now I am already at a relatively elite institution, not exactly lacking for high quality seminars, but nonetheless make the time to listen to KITP seminars (ordinarily from home while using wireless headphones and doing something else, e.g., changing a diaper). I can only imagine how spectacularly useful and important it must be for students and researchers in other parts of the country, and rest of the world, who do not have comparable access to local resources. I wish every institution were set up to provide a similar resource, but at the moment the KITP talk archive remains unique. It fits naturally within the KITP mission; it’s been implemented superbly.”

A spontaneous email to KITP director David Gross from a Case Western Reserve graduate student in physics, Murad Mithani, attests to the usefulness of the talk archive to somebody formerly “without access to local resources.”

Mithani wrote of the talk archive, “I just wanted to thank you and your team for the great contribution that it is making in the lives of so many people."

“To give you an example, I did my undergrad almost 12 years ago in Pakistan. From then on I couldn’t afford to study anymore but always wished for a chance to study more of physics. Before coming to Case this year, during the last 5 years, the only physics professor accessible to me was the Kavli Institute. Every weekend, I would treat myself to a few lectures that would make me see and think about the world outside my world. And now even at age 33, so long after doing my bachelor’s, I still am able to understand most of what is being discussed in physics graduate courses only because the Kavli Institute allowed me to stay tuned to the latest in the world of physics.”

Gross credits the virtual KITP for enabling the brick-and-mortar KITP to remain “in the absolute vanguard of 21st century theoretical physics innovation.”

Noting the disconnect in having a work-a-day homepage as portal to “a wonderland of some of the most far-seeing intellectual content on the web,” Gross said that he had recently asked Eardley to chair a committee (including Stuart Mabon and Simon Raab, successful businessmen and entrepreneurs, who are members of the KITP Director’s Council) to oversee an overhaul of the KITP web site. The mission is to design and implement homepage and user interfaces that accord with the brilliance of the interior offerings.

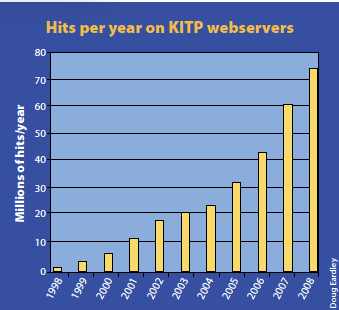

Traffic Tallies

Whatever its homepage impressions, the KITP web site is extraordinarily popular. The total number of hits for the 12-month period ending March 31, 2008, comes to 76,208,536 or about 209,000 hits per day. That annual total is up from the previous year’s total of 62,727,231 and the 2006 total of 44,877,855. The current annual tally of hits represents a roughly 75-fold increase in 10 years from the original annual total of 1,272,123 back in 1998.

Said Eardley, “We can estimate only crudely the proportion of usage by the public at large, in contrast to scientists. We believe this breakdown to be very roughly 50/50 at present based on ratios of hits from .com domains.”

A really striking statistic is the sharp increase in downloads of audio-visual files for the 12-month period ending in March over the previous two years: 8,600,000 downloads in 2008; 2,800,000 downloads in 2007; and 620,000 downloads in 2006.

“The steep increase (quadrupling each year since 2005),” noted Eardley, “follows our introduction of several new kinds of videos and podcasts for each talk.” The speaker’s visuals are available to a listener as a download separate from the audio. These visual files in PDF-format average 25 slides per file. The annual tallies ascended from 393,000 downloads in 2006 to 599,000 downloads in 2007 to 739,000 downloads in 2008.

According to Eardley, “We can measure total bandwidth going out of this place. And we can determine with more difficulty how increasing bandwidth usage pertains to increasing numbers of users. The total bandwidth has doubled every year,” said Eardley.

“The number of users is increasing more slowly by, we think, some 20 to 30 percent a year. Better computers,” Eardley explained, “mean that more data can be downloaded at high quality video feed, so that the number of people downloading is not going up as fast as the actual bandwidth — the bits and bytes — being downloaded. But increasing the number of people who download per year by 20 to 30 percent still means that our growth cumulatively over the past decade has been enormous.”

Transparencies to Start

The first experiment with putting KITP programming on line dates to 1997 with “Supernovae,” held from Aug. 15 to Dec. 15. That program is memorable in retrospect because some participants were then engaged in analyzing the supernovae Type Ia data, which led to the earthshaking conclusion that the expansion rate of the universe is now accelerating. Interestingly, that first effort at on-line programming pertained only to visual information. Eardley recalls, “One staff member collected all the transparencies (those were the days before widespread use of PowerPoint) and scanned them (it took a long time) and then put them onto the ’net.'”

For the second attempt, said Eardley, “We added audio recording to the transparencies so that the audience could hear the talk and see the slides. That program,” Eardley said, “was on ‘Jamming’—a topic pertaining to soft condensed matter systems, such as soap bubbles and grains of sand. If sand is dumped out of a bucket, the flow falters at first and then avalanches. There is a lot of scientific subtlety in that.”

Though an astrophysicist, Eardley in his role of KITP web impresario has heard a lot of talks and snippets of very many more talks on all the other areas of physics, including those interfacing especially with mathematics and biology. Eardley hears so much because he edits every talk.

“What I have tried to do,” he said, “is find out how to edit a one-hour talk with no more than five minutes of editing time. The main thing is to identify where a talk begins and ends. The end is usually signified by applause though there are usually questions that follow, which are often important to include in the on-line version. The other trick is to figure out when the talk begins, which is almost always obvious though most speakers like to warm up with either inconsequential comments or a joke. The joke always presents a problem of whether it is relevant to the talk or not.”

The talks are recorded on two computers to guard against a technical failure in one. “We have had a chronic problem,” said Eardley, “of speakers forgetting to turn on their microphone or of turning it off, so a computer staff member appears at the start of every talk and does a couple of things: makes sure the speaker’s laptop is working and that the microphone to our two recording computers is turned on and operating when the talk begins.”

Video above and beyond copies of transparencies and PowerPoint was instituted in the late ’90s. The cameras were installed initially in the two seminar rooms in the original Kohn Hall building to accommodate video conferencing. Once the cameras were in place, it just seemed obvious that they should be used to record video of the speaker.

Most speakers, using computer-based presentation software to illustrate their words, write little on a blackboard though one of the two fixed cameras in the three seminar rooms is trained to zoom in on writing.

Doug Eardley (l) and Kevin Barron. Photo by Charmien Carrier.

Doug Eardley (l) and Kevin Barron. Photo by Charmien Carrier.

Blackboard Challenge

But the weekly “Blackboard Talks” present a special problem for video recording because speakers are encouraged to make more extensive use of the blackboard as a medium for communication. Intended to break the mold of the speaker’s set talk illustrated with computer-based visuals, these talks are meant to revert to the more traditional pedagogical mode of blackboard because the point of this series is for participants in one KITP program to explain their scientific concerns to participants in another completely different KITP program. To accommodate the special blackboard challenge, Eardley generally operates the cameras himself. “In the almost new auditorium,” said Eardley of the technically well-equipped facility in the 2004 addition where the “Blackboard Talks” generally occur, “each of two cameras looks at part of a blackboard. I have made a bunch of technical tools to try to automate editing together the separate views. I try to do this in five minutes. For a ‘Blackboard Talk,’ it may take 10 minutes. Occasionally, a mistake occurs, and then I have to go back and do a real-time job of editing.” Asked if he plans on marketing his editing software, Eardley said, “I try to give away the software, though it’s hard to give away because then we’re responsible for supporting it.”

Terabyte Rule of Three

How does the KITP back up its terabytes of data representing 10 years of KITP talks? “We do the same thing Google does,” said Eardley. “Google doesn’t back anything up on tape. We have everything on three different hard drives.”

One of the key editorial decisions that was made early on is that the KITP doesn’t own the talk; the speaker does.

“Our original thought,” said Eardley, “was that we wanted to post the talks so that scientists elsewhere could follow as a means of scientific communication, but we soon realized that the talks had huge educational value for the physics and allied science and mathematics communities, as well as for the intelligent lay public who want to learn about science."

“That realization about the identity of our users has helped guide our choice and use of technology. At first we thought we’d use the most advanced technology, but we got cries for help from places like India and Chile where there are sophisticated scientists and great scientific programs, but where the infrastructure is not as good as it is in the U.S. So we decided to provide a choice whereby people can get high bandwidth and low bandwidth versions. We try to provide the most advanced technology, but still have low bandwidth stuff easily available to everyone.”

The virtual KITP benefits participants arriving mid-program. Access to earlier presentations enables latecomers to become current with program content. Also, because talks within programs address edge issues for researchers — i.e., work in progress — the presentations tend to lack the structured clarity of published articles. The virtual KITP enables auditors to go back and hear again intellectually provocative utterances, either not fully comprehended initially or appreciated only in retrospect.

Eardley describes one noted Caltech string theorist reporting how listening to KITP talks via car radio eased the arduousness of the commutes (100-mile+, one-way) between Pasadena and Santa Barbara. (String theory is one of those physics fields where the material is so complex that any given talk by one string theorist is likely not understood by another string theorist [at least on first hearing].)

What enables talks to be heard over the car radio is their availability since 2005 via the KITP web site in Podcast format for downloading to computer based iTunes or Windows Media Player and from there to an iPod or other MP3 player, whose output can in turn be played over a radio via wireless or wired transmission.

Despite the availability of new formats, a large number of users still download KITP talks in their original Real Audio format. The other popular format is Quick Time. Said Eardley, “I thought Real Audio was a ‘sunset’ niche product that would by now have sunk below the user horizon, but that just hasn’t happened.”

Early on in the history of the virtual KITP, Eardley contemplated the prospect of recording the talks in full video as does the Mathematical Sciences Research Institute (MSRI), an NSF-funded facility, akin to the KITP, located on the Berkeley campus. But he opted initially for the limited video of transparencies and PowerPoint. Anyone who has “watched” a KITP talk, since the cameras have been running in the seminar rooms, knows that the video coverage is intermittent. That approach makes smaller files that are amenable not only to fast download, but also for eventual transfer to an iPod-like portable player.

What does Eardley see as the next innovation?

“We have to do the YouTube format, Adobe Flash Technology.”

Virtual KITP Top Ten

What talks number among the Virtual KITP Top Ten?

Two of the first three public lectures dating back to 1998 turn out to be the most popular: Edward Witten of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton on “Duality, Spacetime and Quantum Mechanics” and MIT’s Wolfgang Ketterle on “A New Form of Matter: Bose-Einstein Condensation and the Atom Laser.” Interest in the Ketterle public lecture surged when he won the 2001 Nobel Prize in Physics.

Of the staple fare for scientists, the 2001 program with the seemingly nondescript title “Statistical Physics and Biological Information” tops the KITP bestseller list. “Thousands of people are still listening to those talks after all these years,” said Eardley, who notes that biologists especially “love the medium” of the virtual KITP.

Programs with large pedagogical content — giving physicists access to biology and biologists access to physics — have what Eardley calls “the longest legs.” All of the biophysics programs have legs that are long, as do the mathematical programs with again that pedagogical component designed to bridge the disciplines of mathematics and physics.

Interestingly, the most popular of the KITP mainstay talks are also the most interdisciplinary.