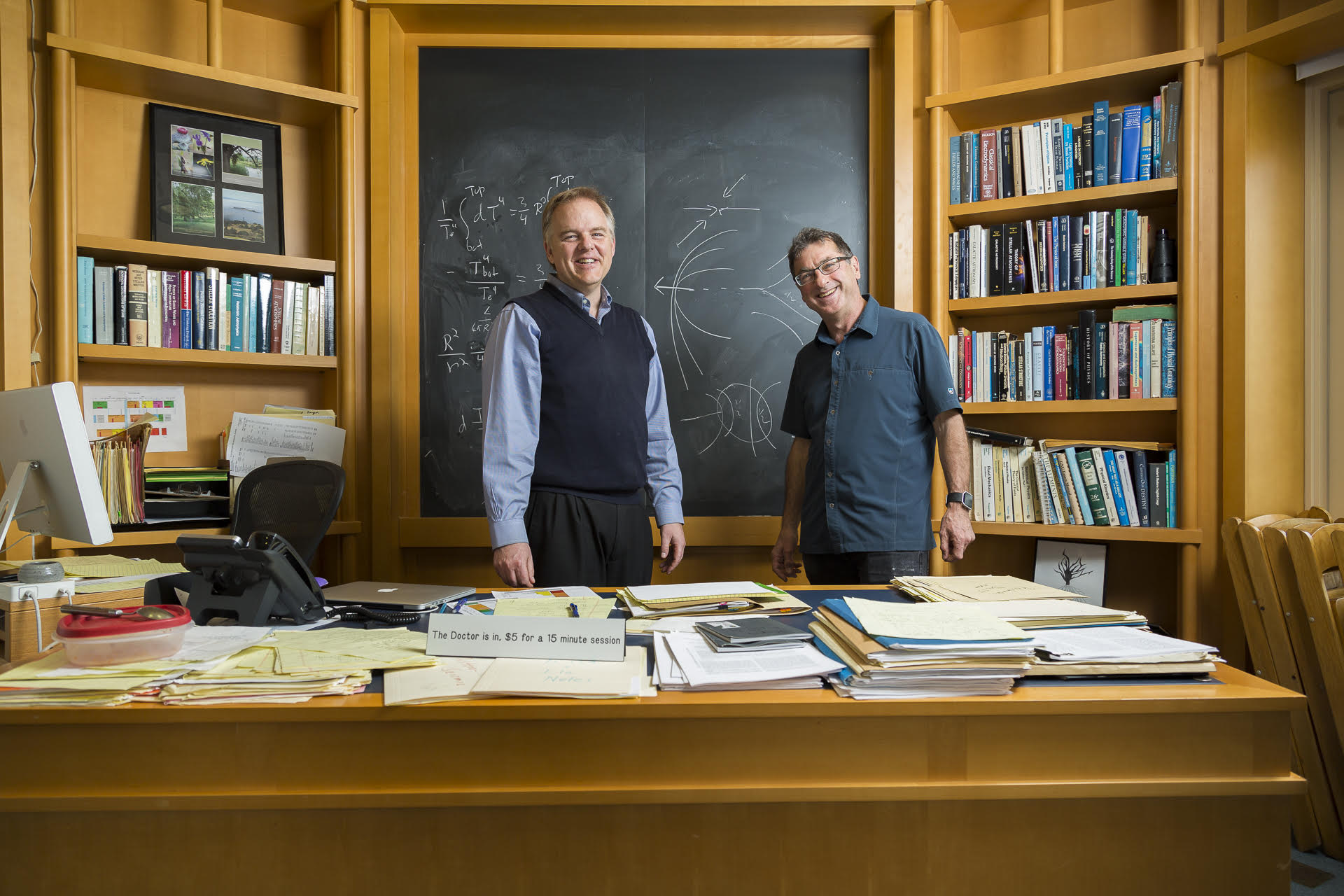

KITP Director Lars Bildsten and Deputy Director Mark Bowick

KITP Director Lars Bildsten and Deputy Director Mark Bowick

CREDIT: MATT PERKO

Our Senior Director of Development Kristi Newton interviewed KITP Deputy Director Mark Bowick virtually this Spring to talk all things KITP. An accomplished condensed matter and high energy theorist and a Visiting Distinguished Professor in the UCSB Physics Department, Mark brings his expertise, inspiration and a great sense humor to the role of Deputy Director.

Q: What is the role of the Deputy Director at KITP?

A: I help to curate scientific aspects of our KITP programming which is a two-year process. I vet and help to support pre-proposals from the science community, and then work with the KITP Advisory Board to develop full proposals for submissions that have the most merit. Of these, 10-12 are chosen to be our future programs. Right now we have just decided on the programs for the 2022-23 program year.

I then work with program coordinators and our KITP Program Manager David Kaczorowski to facilitate program invitation lists, which we review carefully to ensure there is diversity at multiple levels. Together with the Director Lars Bildsten and the other KITP permanent members, we then work proactively with program coordinators to ensure that programs are successful from launch to completion, and beyond. Lars and I have a planning meeting with coordinators before each program begins, to share what we have learned over the years. This helps to make programs more successful and also allows us to check on the balance between formal presentations and discussion time. I often follow how programs are doing by taking part in their formal and informal activities.

A very enjoyable part of my job is to help curate the diverse variety of outreach and community events we host in partnership with Kristi and Megan, our great Development Team; from “Public Lectures” for a broad audience, smaller “Chalk Talks” and coffees with scientists for our Friends of KITP and supporters, to “Café KITP” and our recently-launched “Big Ideas” series, featuring our outstanding postdocs presenting their research or sharing key ideas or challenges in their field with the community.

One of the many great things about being the Deputy Director here is that everyone at KITP is very good at what they do. It’s a great team to work with and this makes my job a lot more fun!

Q: How has your role changed (if at all) because of the pandemic?

A: In March of 2020, we had to “redo” our two-year process for curating collaborative programs at KITP and switch to an online mode. We were mid-stream in planning when the pandemic hit and we had to adjust our plans quickly. We contacted all of the upcoming program coordinators and determined which programs were enthusiastic about going virtual. Participants then had to be contacted and the timetable revised.

As luck would have it, I happened to be a coordinator for the first program that went virtual a few weeks later. It was a 9-week program on Active Matter that was completely redesigned to run virtually. We were able to experiment and learn what worked and what didn’t work, and to share these lessons and build on them with future online programs.

Q: What do you like most about being Deputy Director?

A: I like that the role is very broad, which fits with my having worked on a wide variety of science topics throughout my career. It’s great to be able to participate in all of the aspects of science that the KITP conducts. The vast majority of the world’s leading scientists come to the KITP at some point and often very frequently. I used to say (pre-Covid) that I couldn’t even make it to the coffee machine without running into a top-notch scientist! Outreach is fun and challenging, too.

Q: Tell me about your current research.

A: I am interested in how order develops and its relation to symmetry. The world around us shows us a variety of behaviors from being very ordered to very disordered, and everything in between. There are many examples of how matter transitions from being structureless to having structure associated with order.

There are also inevitable and striking irregularities in every ordered structure – from atomically thin sheets of graphene to the large-scale distribution of galaxies. These essential singularities, or defects, are often described by the field of topology in mathematics and so we call them topological defects. They were discovered in liquid crystals, such as those used in modern liquid crystal displays (LCDs), in the late 19th century. I am particularly interested in topological defects in active liquid crystals – those that locally consume energy.

I am also trying to understand what happens to ultra-thin materials, like graphene, when heated up. Their behavior when warm is profoundly different from their behavior at zero temperature and it is all controlled by temperature and geometry. It’s fascinating!

Q: What inspires you?

A: The power of thought inspires me. I find it amazing that we can explain anything at all. Most of us got into science because we were curious about the world around us and wanted to figure out how things work. The power of deductive – and inductive – reasoning is striking when it actually works! But most of our work is a big puzzle. We never really know how it’s going to turn out or whether there is even an answer. That can be uncomfortable, so it’s a subtle balance.

Q: If you could change one thing about physicists, what would it be?

A: We physicists are not one uniform species, thank goodness! We are all really different in terms of approach, personalities and skills. As a community we could definitely be more diverse in all meanings of the term from gender to race to career-stage, and beyond. This is a big area of focus for us at KITP. We also have a fairly distinctive way of actively engaging with each other and asking probing questions that can be seen as “aggressive” or “intimidating”- this could likely be made more welcoming.

Q: Have you ever considered writing a book? If so, what would it be about?

A: Yes – I have two ideas for a book. One would be about the topological defects I mentioned earlier, emphasizing the very wild things that happen with these defects. They are found everywhere in the physical and mathematical world. The other book would be about soft matter in general—emphasizing some of the intriguing principles of soft matter that are not widely known.

Originally from New Zealand, Mark’s natural habitat is on a boat

Originally from New Zealand, Mark’s natural habitat is on a boat

CREDIT: MARK BOWICK

A: We had a collision in a race. Before you start a race everyone sails around in the harbor tuning up and gauging the wind and currents. On this day there were three of us on the boat. Our skipper was at the helm and two of us were prepping for the race and managing the sails.

All of a sudden there was a huge thump and another boat’s mast crashed down on our deck along with tons of rigging. It was quite a scene! There were five people on the other boat, but somehow no one on their boat saw us, and we didn’t see them either. Sails are poor windows.

Thankfully no one was hurt, although one person on the other boat did go overboard. The ironic thing is that the other boat was so badly damaged that the owner bought a new boat, which now consistently wins the races in our fleet.

Q: Finally, what does it take to run a successful program? How does KITP evaluate for and define success?

A: Despite KITP being known for its relaxed collaborative environment, nothing we do at KITP is by chance--it is all carefully considered and curated. We talk a lot to coordinators and participants about how their program is going along the way and then we have an exit interview with all coordinators and we also ask participants to provide feedback. The main question we ask is “How can we do things better? What could be improved?” It’s a constant evolution. We are always looking to improve.

It will be interesting to see how the changes we have made in adapting to online programming will impact what we do in the long-term. We have learned that online programs allow us to be much more inclusive. The future is likely going to be that if scientists are not able to participate in-person and travel to Santa Barbara, we will invite them to participate virtually so we are always able to give people a way to participate. It has been amazing to see how resourceful our science colleagues have been helping us to figure out how to do things well in a virtual mode. When people are forced in to challenging constraints it generates lots of innovation!