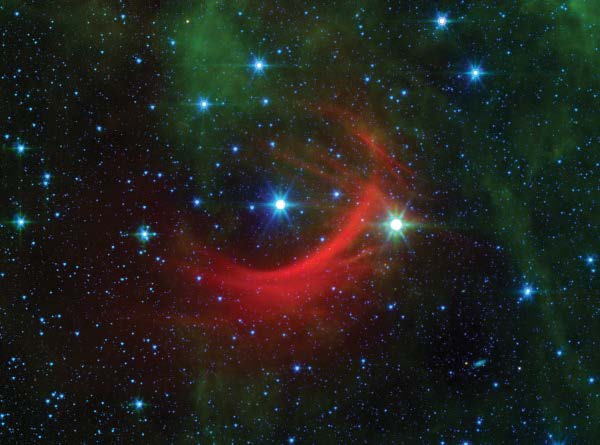

A massive, hot supergiant, Kappa Cassiopeiae is surrounded by a streaky red glow of material in its path called bow shocks, often seen in front of the fastest, most massive stars in the galaxy.

A massive, hot supergiant, Kappa Cassiopeiae is surrounded by a streaky red glow of material in its path called bow shocks, often seen in front of the fastest, most massive stars in the galaxy.

Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech

How I wonder what you are.

From the moment humans first beheld the stars in the night sky, people have sought an answer to that line in the well-known English lullaby.

“Humans have always tried to understand what the lights in the sky are as well as their meaning and function,” Matteo Cantiello, an astrophysicist at UC Santa Barbara’s Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics (KITP), told the standing-room-only crowd at SOhO restaurant in Santa Barbara last April.

They had gathered for the inaugural Café KITP, a series whose motto is “Eat, THINK, and be merry!” to hear Cantiello’s talk on “Music of the Spheres: The Secret Songs of the Stars.”

For Cantiello, the stars are singing astonishing songs. The music begins with oscillations that travel many light-years to reach Earth. Precious information about a star’s deep core comes from oscillations created when the star is shaken by its own turbulent outer layers. The sound of these oscillations can be brought into the range of human hearing by shifting the pitch several octaves.

Despite their distance, stars have a greater connection to us than we might realize. In fact, as Cantiello noted, the elements of which we are made have also been produced inside a star. “Stars are not only the building blocks of the universe,” he said, “but they play a very important role in the chemical evolution of the universe, and they tell us how life as we know it came to be.”

Café KITP came to be as a collaboration between the KITP and its journalist-in-residence, Ivan Amato, a science and technology writer, editor and communicator based in Silver Spring, Maryland. In May 2011, Amato began the quasi-monthly DC Science Café at the local restaurant and cultural hub, Busboys and Poets, to experiment with more direct engagement with the public.

“One of the drivers for me is that science is part of culture, not apart from it,” said Amato. “I think the greatest gift that science has to offer is really the invitation to experience awe as science reveals how nature works.”

It is awe-inspiring, indeed, to realize, as Cantiello pointed out, that stars are similar to humans, not only because both contain common elements, but also because both live and breathe and die.

He went on to explain that since 2009, NASA’s Kepler space observatory has been surveying a portion of our region of the Milky Way galaxy to discover Earth-size planets in or near the habitable zone and determine how many of the billions of stars in our galaxy have such planets. To date, Kepler has discovered more than 3,800 planet candidates and confirmed 961 planets.

“Potentially habitable planets seem common,” said Cantiello. “But it’s a question of life versus intelligent life.” So hundreds of thousands of years after first contemplating the night sky, humans are still wondering about the secrets of the stars.

“KITP has been instrumental in advancing astrophysics as a whole, and in nucleating some of the recent excitement in the area of asteroseismology,” said Greg Huber, deputy director of KITP. “What the KITP is really good at is bringing researchers together from around the world and creating for a period the world’s greatest academic department in one particular area. And we’ve done that for the field of astrophysics.”

Café KITP takes place every few months. For information about dates and topics, visit the KITP website at www.kitp.ucsb.edu/outreach/cafe-kitp.

- Julie Cohen, UCSB Public Affairs & Communication

KITP Newsletter, Winter 2015